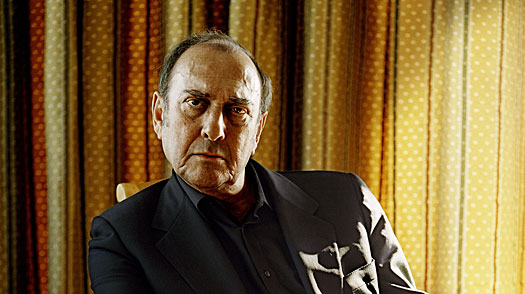

Harold Pinter in 2003

He had the rare honor of earning his own adjective: Pinteresque, that distinctive mood of unnamed menace that permeated his work. In great plays like The Birthday Party, The Caretaker and The Homecoming, Harold Pinter, who died on Dec. 24 at 78, helped unmoor theater from its social-realist traditions, exposing a deep sense of unease beneath ordinary surfaces. Unlike his forebear Samuel Beckett, whose plays were set in an abstracted no-man's-land, Pinter placed his in homely, utterly familiar settings — a rooming house, a family gathering — before kicking out the usual struts of family feeling, human compassion, even logical action. He was famous for his pauses (inspired, he once said, by Jack Benny), but in fact it was his stinging, elliptical, poetically precise dialogue that packed the punch.

Born in London, the son of a Jewish tailor, Pinter was a lifelong leftist, and the specters of nuclear war and totalitarian mind control hung over his work; he used his acceptance speech for the 2005 Nobel Prize for Literature to denounce the war in Iraq. But it was less his politics than his portrayal of our shared existential predicament that made him the most influential British playwright of the past half-century.

—Richard Zoglin